A Washington-based business research group recently conducted an international poll of senior human-resources managers: 75% said that “attracting and retaining” talent was their number one priority. They also surveyed 4,000 hiring managers in more than 30 companies, and were told that the average quality of candidates had declined by 10% since 2004 and the average time to fill a vacancy had increased from 37 days to 51 days; more than one-third of the managers said they had hired below-average candidates “just to fill a position quickly”, and one in three employees had recently been approached by another firm hoping to lure them away.

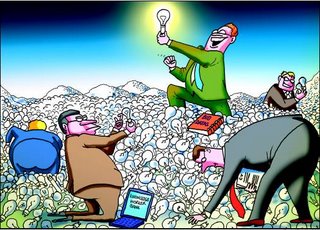

Talent has become the world’s most sought-after commodity, and the shortage is causing serious problems, says Adrian Wooldridge in The Economist, reporting on The Battle For Brainpower. “In a Harvard-University speech in 1943, Winston Churchill observed that ‘the empires of the future will be empires of the mind’. He might have added that the battles of the future will be battles for talent—among companies, and among countries (which fret about the ‘balance of brains’ as well as the ‘balance of power’).”

Google has assembled a formidable hiring machine; Yahoo! has hired a constellation of academic stars, and companies are suing people who suddenly leave. But simply stocking up on talent, and hiring the best and the brightest is not enough. Enron hired 250 MBAs a year at the height of its fame. It applied a “rank-and-yank” system of evaluation, showering the alphas with gold and sacking the gammas. And it promoted talent much faster than experience. Long-Term Capital Management, boasted MBAs and Nobel prizewinners among its staff. Yet both companies succumbed to greed and mismanagement, proving that what’s more important is the management of talent: rewarding both experience and talent, and applying strong ethical codes and internal controls.

So what has made talent ever so important? Structural changes, for one, like the rise of intangible but talent-intensive assets. Baruch Lev, professor at NYU, argues that “intangible assets”—skilled workforce, patents, know-how—account for more than half of the market capitalisation of America’s public companies. Accenture, a management consultancy, says intangible assets have shot up from 20% of the value of companies in the S&P 500 in 1980 to 70% today. And McKinsey says American jobs emphasising “tacit interactions” (complex interactions requiring a high level of judgment) now make up 40% of the American labour market and account for 70% of the jobs created since 1998. And the same sort of thing is bound to happen in developing countries as they get richer.

Other changes:

- Ageing of the population (as baby boomers retire, companies will lose large numbers of experienced workers over a short period), which means everyone will have to fight harder for young talent, as well as learning to tap and manage new sources of talent.

- Loyalty to employers is also fading. Thanks to downsizing, the old social contract—job security in return for commitment—is breaking down.

- Obsession with talent is no longer confined to blue-chip companies, and has gone global.

- Multinational companies have shipped back-office and IT operations to the developing world, particularly India and China. More recently they have started moving better jobs offshore as well, capitalising on high-grade workers with local knowledge; but now they are bumping up against talent shortages in the developing world too.

- Even governments have got the talent bug. Rich countries have progressed from relaxing their immigration laws to actively luring highly qualified people. Most of them are using their universities as magnets for talent.

- And India and China are trying to entice back some of their brightest people from abroad.